First snapshots of trapped CO2 molecules shed new light on carbon capture

A new twist on cryo-EM imaging reveals what’s going on inside MOFs, highly porous nanoparticles with big potential for storing fuel, separating gases and removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Scientists from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University have taken the first images of carbon dioxide molecules within a molecular cage – part of a highly porous nanoparticle known as a MOF, or metal-organic framework, with great potential for separating and storing gases and liquids.

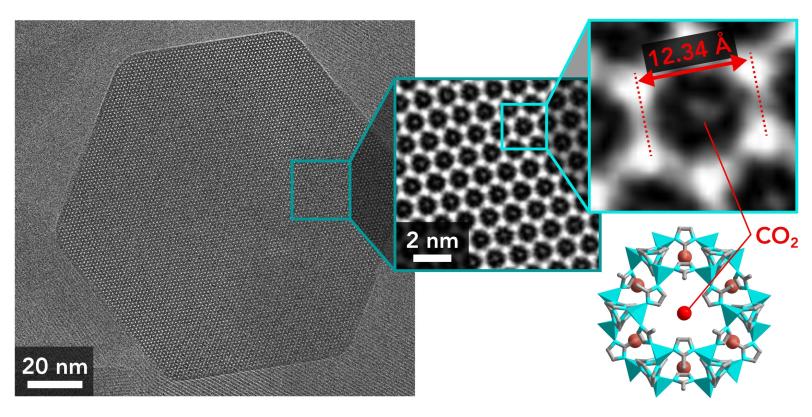

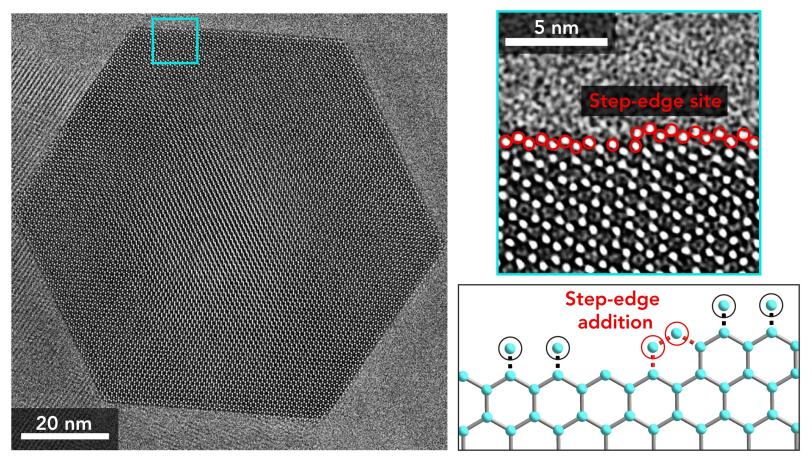

The images, made at the Stanford-SLAC Cryo-EM Facilities, show two configurations of the CO2 molecule in its cage, in what scientists call a guest-host relationship; reveal that the cage expands slightly as the CO2 enters; and zoom in on jagged edges where MOF particles may grow by adding more cages.

“This is a groundbreaking achievement that is sure to bring unprecedented insights into how these highly porous structures carry out their exceptional functions, and it demonstrates the power of cryo-EM for solving a particularly difficult problem in MOF chemistry,” said Omar Yaghi, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley and a pioneer in this area of chemistry, who was not involved in the study.

The research team, led by SLAC/Stanford professors Yi Cui and Wah Chiu, described the study today in the journal Matter.

Tiny specks with enormous surfaces

MOFs have the largest surface areas of any known material. A single gram, or three hundredths of an ounce, can have a surface area nearly the size of two football fields, offering plenty of space for guest molecules to enter millions of host cages.

Despite their enormous commercial potential and two decades of intense, accelerating research, MOFs are just now starting to reach the market. Scientists across the globe engineer more than 6,000 new types of MOF particles per year, looking for the right combinations of structure and chemistry for particular tasks, such as increasing the storage capacity of gas tanks or capturing and burying CO2 from smokestacks to combat climate change.

“According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, limiting global temperature increases to 1.5 degrees Celsius will require some form of carbon capture technology,” said Yuzhang Li, a Stanford postdoctoral researcher and lead author of the report. "These materials have the potential to capture large quantities of CO2, and understanding where the CO2 is bound inside these porous frameworks is really important in designing materials that do that more cheaply and efficiently.”

One of the most powerful methods for observing materials is transmission electron microscopy, or TEM, which can make images in atom-by-atom detail. But many MOFs, and the bonds that hold guest molecules inside them, melt into blobs when exposed to the intense electron beams needed for this type of imaging.

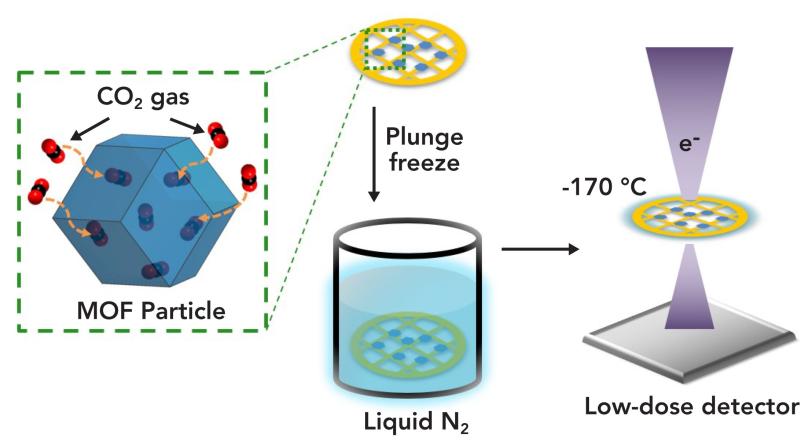

A few years ago, Cui and Li adopted a method that’s been used for many years to study biological samples: Freeze samples so they hold up better under electron bombardment. They used an advanced TEM instrument at the Stanford Nano Shared Facilities to examine flash-frozen samples containing dendrites – finger-like growths of lithium metal that can pierce and damage lithium-ion batteries – in atomic detail for the first time.

Atomic images, one electron at a time

For this latest study, Cui and Li used instruments at the Stanford-SLAC Cryo-EM Facilities, which have much more sensitive detectors that can pick up signals from individual electrons passing through a sample. This allowed the scientists to make images in atomic detail while minimizing the electron beam exposure.

The MOF they studied is called ZIF-8. It came in particles just 100 billionths of a meter in diameter; you’d need to line about 900 of them up to match the width of a human hair. “It has high commercial potential because it’s very cheap and easy to synthesize,” said Stanford postdoctoral researcher Kecheng Wang, who played a key role in the experiments. “It’s already being used to capture and store toxic gases.”

Cryo-EM not only let them make super-sharp images with minimal damage to the particles, but it also kept the CO2 gas from escaping while its picture was being taken. By imaging the sample from two angles, the investigators were able to confirm the positions of two of the four sites where CO2 is thought to be weakly held in place inside its cage.

“I was really excited when I saw the pictures. It’s a brilliant piece of work,” said Stanford Professor Robert Sinclair, an expert in using TEM to study materials who helped interpret the team’s results. “Taking pictures of the gas molecules inside the MOFs is an incredible step forward.”

Major funding for this study came from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Energy.

Citation: Li et al., Matter, 26 June 2019, (10.1016/j.matt.2019.06.001)

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.